Vermin vs Vengeance: The Real House of the Dragon Rat Catchers

🚨 HOUSE OF THE DRAGON SPOILERS AHEAD 🚨

The Black Plague was medieval Europe’s darkest nightmare, but it was one community’s brightest future. The humble rat catcher.

What began as a curious Google search into the very real and intriguing history of rat catchers ended in a profound historical mystery that until recently was heralded as a medieval myth.

This week’s Substack was inspired by the brilliant premiere episode of House of the Dragon (HOTD) Season 2. So be forewarned of spoilers ahead!!

HOTD has finally graced our bard box (TV) after what seemed like 20 moons ago and it began with a bang, not a whisper…or rather a slice. Too soon?

As a book reader, I was fully aware of the dreaded Blood and Cheese moment. Yet I was still not prepared for the gruesome act that followed.

But that is not what I want to focus on today. My fellow HOTD compeers, I have gone down the proverbial rabbit hole about the surprisingly compelling history behind royal rat catchers.

And apparently today is the absolute perfect day to discuss this because June 26th just happens to be ‘Happy Rat Catcher’s Day’. Why June 26th? Well that is the billion dollar question that historians are still answering to this day and is the crux of the mystery to come later in the article.

But first, let’s talk rat catchers.

During medieval times, and beyond, the scale between man and vermin tipped precariously, and uncomfortably I might add, in the direction of creatures of all kinds, but especially rats.

For better or for worse, rats did not discriminate between prince or pauper and managed to claw their way to the very top of society.

The same went for King’s Landing, the fictional kingdom that exists within the world of George R.R. Martin’s ‘A Song of Ice and Fire’ series.

From what we can gather from Martin’s many interviews, King’s Landing is a representation of medieval England and true to its real history, England was reeling from rats.

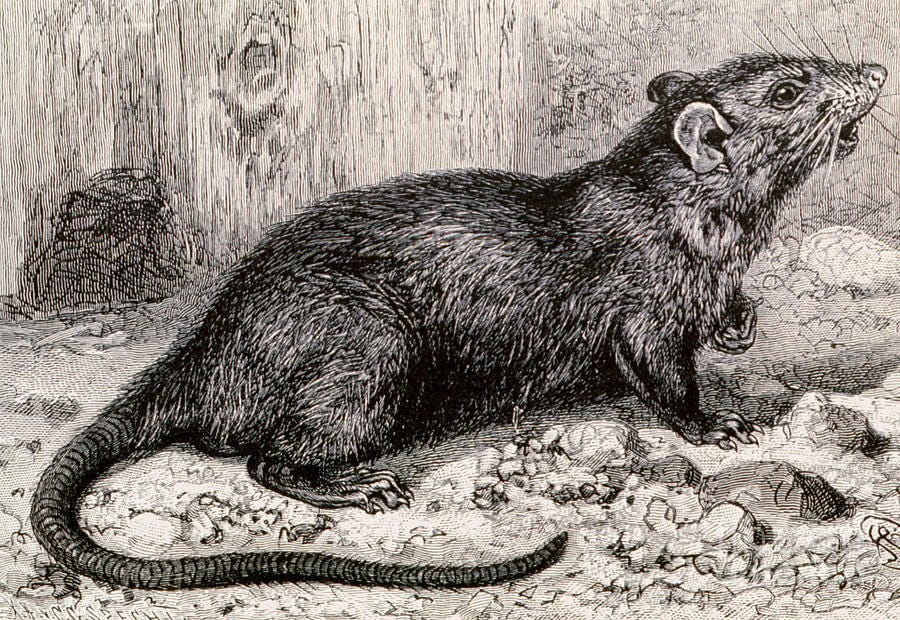

As author and historian Paul Cowdell aptly stated, “In London you’re never more than 10 feet from a rat.” Rats have been a longstanding issue in Britain since the days of Roman Rule, but it was during the medieval era that their presence became a problem of the plague variety. Thus the role of the rat catcher was born.

Historically, rat catchers were humble, common folk who figured they might as well get paid to do a job they were already doing on a daily basis. Many utilized various methods to eliminate vermin. Poison, traps, animals like dogs or ferrets to catch or kill rats all in the name of preventing serious public health risks, particularly the spread of diseases. Some even got slyly entrepreneurial and would breed the rats they caught in order to release and catch them for even more pay.

Now, this is where I have to tip my hat to the researchers on HOTD because they portrayed the rat catcher starter pack to a T. Not to mention the nickname “Cheese” for a rat catcher.

‘Cheese, the first of his name, lurer of rats and now slayer of princes.’

A classic rat catcher would be found carrying a box slung over one shoulder, a long stick with a cage at the end for trapped rats and a dog.

The typical rat catcher was often nomadic, traveling from town to town in search of employment.

Despite their vital role in maintaining the health and sanitation of medieval communities, rat catchers were often regarded with disgust, disdain or simply ignored altogether and left at the fringes of society because of their proximity to vermin.

Yet that all changed after the Black Death or Bubonic Plague decimated a third of the European population in the 14th century. Rat catchers emerged as heroes after this grim period, serving as essential figures in medieval towns and villages.

Although the scientific connection between rats, the fleas they carry, and transmission of deadly disease would not be discovered until centuries later, there was still a clear understanding that rats were spreading sickness and therefore must be done away with.

This was when dogs became a rat catcher’s greatest tool.

Specially trained dogs, usually rat terriers, were skilled at finding and killing rats and became invaluable at controlling rat populations. Dogs could go where the traps couldn’t and could sniff out a hiding rat with ease.

Yet, the height of rat catching wouldn’t be until Victorian Era England.

The rapid growth and expansion from the Industrial Revolution provided the perfect conditions for an explosion of rats to bubble to the surface. Consequently, rat catchers finally became an organized industry with uniforms to boot, but at the same time, the medieval perception of rat catchers also came back. Rat catchers were seen as shifty characters always lurking in the London shadows with a vast knowledge of the city’s dark underbelly.

One rat catcher who endeavored to overcome that stereotype became one of the most famous rat catchers of all time and his name was Jack Black, the official rat catcher for Queen Victoria herself.

Black was quite the character and was often seen in his rat catching costume of white leather pants, green coat, scarlet waistcoat and a rat belt buckle that he commissioned for himself.

Black was a quirky sort. In addition to catching and killing royal rats, he also bred what were known as ‘fancy rats” or pet rats that rich Victorians would keep in gilded cages.

He became known across London for breeding unusually colored rats and selling them as “designer vermin” to notable Victorian high society including Beatrix Potter, the author of the Peter Rabbit series, and Queen Victoria herself.

But by far the most legendary rat catcher of all time, which even has its own holiday, is the medieval myth of the Pied Piper of Hamelin.

We have now finally come to the crux and purpose of this story…

Thank you for being a subscriber to Today I Learned Science’s Substack. You’ve come to the end of the free preview. Please consider becoming a paid subscriber to support Dr. Bhat’s work, so she may continue to bring high quality deep dives into science & history to your inbox. Enjoy!

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Today I Learned Science to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.