Interview with Key MH370 Investigator

Jean-Luc Marchand believes he knows where the plane is and why

The missing Malaysian Airlines flight MH370 has come back into the news full force and for good reason.

Independent expert investigators have dedicated their time and knowledge to solving this 10 year old mystery in hopes of providing closure and answers for the world.

One of the key investigators whose groundbreaking research led to the MH370 search being reopened is a man named Jean-Luc Marchand and I had the immense pleasure of interviewing him.

Jean-Luc was part of the European Space Agency in the Netherlands and from there was seconded to the European Commission to ensure that the air traffic management perspective was taken into account in the development of new flying vehicles. Now partially retired, he has dedicated his time, voluntarily, to investigating MH370 with real success.

Without further ado, here is a preview of our conversation:

The interview started off with a bang.

My typical first question is: How did you start investigating this case?

I was NOT expecting his answer.

When MH370 went missing on March 8th, 2014, Jean-Luc was working at EuroControl and got pulled onto an initiative called CASPIO, whose entire mission was to investigate a possible hijacking of the plane by an external group of people.

He spent months investigating this scenario because, initially, everyone truly thought that the plane was taken over by a third party hijacker based on the limited information given.

Jean-Luc explained the reason they went that route was because the industry was being cautious and didn’t want to immediately point fingers at the pilot. They needed to eliminate all other lines of inquiry first.

But after a few months of investigating, it soon became evident to Jean-Luc that an external hijacker scenario wasn’t answering all the questions.

For one, if it was a hijacking there would’ve been terms for negotiations for the hostages or an attempt to escape and land at a different airport, none of which happened.

Eventually, Jean-Luc was introduced to Captain Patrick Blelly, a retired French pilot, who dared to investigate the elephant in the room - that it was not someone external, but someone inside the plane, most likely the pilot, who was responsible.

So the two teamed up and have been working together ever since to solve the disappearance of MH370 and it looks like they finally have.

Two months ago I interviewed Richard Godfrey, a retired aerospace engineer, who used WSPR data (a type of weak radio signal data) to find the crash site of MH370.

Jean-Luc used radio signals as well, but three different types of radio signals to essentially triangulate the true flight path and crash site of MH370.

I will tell you right now that the location of Jean-Luc’s crash site is different to Richard Godfrey’s.

(If you haven’t read my interview with Godfrey about his key research of MH370, you can read it here.)

Not to say one is right or wrong, because we won't know until we find the plane, but they are different.

Jean-Luc gets into why that is in the interview.

But before we jump into that, let’s start from the very beginning.

40 minutes into the flight, Malaysian ATC checked in with flight MH370 once the plane entered Vietnamese airspace at the IGARI waypoint near Ho Chi Minh.

Malaysian ATC sends MH370 a routine message, “Malaysian 370 contact Ho Chi Minh one two zero decimal niner, good night.”

One of the two captains aboard, Captain Zaharie Shah, replied “Good night” at 17:19:30 UTC.

(If you’d like to hear the final radio messages instead click here.)

And those were the last words heard from flight MH370 before it disappeared.

Because just 66 seconds later, the transponder symbol for MH370 vanished off the radar display. Malaysian Airlines Flight MH370 had officially and suddenly gone “dark”.

Q: So what happened at IGARI? How can a Boeing 777, like MH370 go completely dark, off the radar? How does something like that happen?

The answer has to do with the radars.

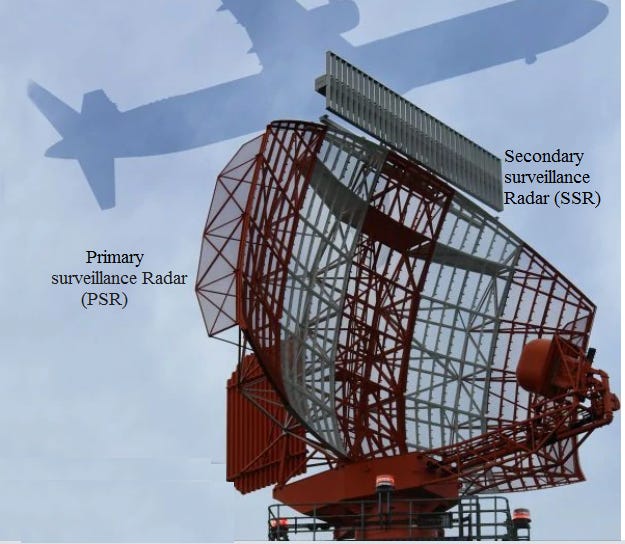

Now there are 2 types of radars involved with the airline industry. The first is called a primary radar, which sends a ping and receives an echo. This type of radar is more passive.

The second is something called a secondary surveillance radar or SSR, but I’ll just refer to it as the secondary radar. This system is proactively assessing the plane and gathering real time data about the aircraft.

Both primary and secondary radars are typically located near airports on land. The land part is key. In the ocean it’s a different story, but on land these two radars exist together.

This system is how air traffic control (ATC) for commercial flights get confirmation that an aircraft exists and where it’s going at any given point in time.

But there’s a caveat.

The primary radar, as I mentioned, provides pretty basic info. It sends out a ping, receives an echo back. So for example, if there are two planes crossing near each other, both planes will ping back to the primary radar, but the radar can’t tell you which plane the echo came from.

Meanwhile, secondary radar gives you all that information. It tells you which plane is which and what direction it’s coming from whether that’s left, right, up or down to properly identify the aircraft.

But in order for the secondary radar to work, you need a complimentary system onboard the airplane called a transponder.

If there is no transponder then the secondary radar won’t work. It becomes completely blind.

And THAT distinction is important.

Because like any system there are limitations when it comes to receiving a signal. There are limits to these radar receptions, which can cause gaps in information.

And that brings us to IGARI.

After IGARI the secondary radar stopped receiving information which means that the transponder must have stopped working. The initial thought was that it was due to a power failure. But after Jean-Luc looked at the radar data, it was clear that was not the case at all.

How does he know that with such certainty?

Before MH370 went dark, the transponder relayed several messages to the ground of different statuses. Think of it like instant messenger or any chat platform.

You have your active ‘I’m online’ status message, then your away message is a different status and then another message when you’re offline.

That’s exactly what happened with the MH370 transponder. These three different status messages were sent to the ground.

If it was a power supply cutoff, then there would be no time for any messages to be sent out. The signal would’ve stopped abruptly. Instead there is a clear degradation of information as seen by the different status messages sent out from MH370 to the ground.

This means that the transponder, which is a physical knob, was manually turned and switched off at the control panel in the cockpit by somebody.

As a result, the ATC was left with only the primary radar, which we’ve established is not very helpful on its own.

But here’s where things get really interesting or eerie depending on how you look at it.

If an aircraft gets lost, the secondary radar will take the previous echoes, the flight plan and route and create a forecast of the plane’s most likely trajectory for up to 4 more pings, which is what it did for MH370.

But after IGARI, even the primary radar stopped working because the plane’s signal went out of reception.

Based on the radar data and the gaps in radar data - because the lack of information is just as critical here, Jean-Luc was able to deduct that the aircraft was actively descending at this point.

In other words, after MH370 went dark, it also escaped the primary radar because it suddenly dropped low enough to be hidden by mountains.

All the above paints a rather grim picture and answers one of the most important and common questions people have about MH370, which is…

Q: How did no one on the plane try to stop what was happening?

After it was made clear that the plane was no longer enroute to its intended destination of Beijing, surely some passengers and certainly the flight attendants would have protested?

The answer is not something we’ve not had confirmed in such detail.

After MH370 turned, the pilot likely jumped into action to do several things at once.

They switched off the transponder, cut the power, depressurized the cabin and sent the plane into a sudden drop to mimic a hijacking and emergency descent.

All of the above achieved several things. Cutting the power prevented anyone in the plane from contacting the ground and depressurizing the cabin kept people seated and quiet. The latter also took care of the flight attendants. Flight attendants are highly trained individuals and in emergency or crisis situations they don’t think, they act.

As soon as a plane becomes depressurized, masks fall and coupled with a descent, the immediate procedure is for the flight attendants to help everyone get their mask on and do what they can to assist in the emergency. They’re certainly not knocking on the cockpit door thinking the pilot is doing something nefarious.

But the copilot is a different story.

According to Jean-Luc, the co-pilot’s procedure would be to grab a portable oxygen bottle and return to his seat in the cockpit.

Did the copilot discover what was happening inside the cockpit and try to stop it or was the cockpit door already locked by the time he got to it?

Unfortunately, I don’t think we will ever know the answer to that even if we do find the plane.

But, what we do know is that once MH370 passed over the Malaysian island of Penang, the copilot’s phone turned on for a few seconds.

Jean-Luc’s interpretation is that the copilot attempted to call the ground for help at this point, but the call couldn’t go through.

I used to live in Penang and flew from Kuala Lumpur (KL) to Penang and vice versa many times. While Jean-Luc was talking I did the quick math in my head.

The oxygen masks that deploy in an emergency situation provide oxygen for around 20 minutes. The flight time from KL to Penang is approximately 1 hour, so by this point everyone on board likely had fallen into hypoxia, if not already dead.

Whoever did this planned it meticulously, knowing the entire flight would all be in a hypoxic state by the time they reached Penang and is probably why they turned the power back on at this point temporarily, hence why the copilot’s phone briefly connected.

But there was still an unanswered question that was bugging me. So, I asked Jean-Luc.

Q: Why switch off the transponder at IGARI? Why not switch it off at a later point? Is there something special about that region in particular?

Turns out there is.

“If you want to disappear and never be found, this is where you would do it.” Jean-Luc responded.

He explains this is due to a few reasons.

Firstly, the primary radar forecasts every 30 min based on the last checkpoint, which in MH370’s case is IGARI. The forecast is partially based on the filed flight path, which was to Beijing. So, the pilot intentionally switched off the transponder after IGARI knowing all this to buy time.

Because based on the primary radar forecast, ATC believed that MH370 was still on its planned route heading towards Ho Chi Minh on the way to Beijing. As a result, the search and rescue zeroed in on the South China Sea for the first critical hours.

It was only discovered much later via military data that in reality, MH370 took a sharp U-turn back towards the Malay peninsula right after checking in at IGARI.

The second reason is geographical

IGARI is under Vietnam’s ATC, north east of that is Taiwanese ATC and below is Singapore’s ATC. However, during peacetime Singapore’s airspace falls under Malaysia. That is really important and why less than 60 seconds after IGARI, the pilot U-turns sharply into Singapore’s airspace” because it is under Malaysia ATC’s responsibility.

But here’s why it’s so diabolically clever.

IGARI was meant to be Malaysian ATCs last check in with MH370. There are so many planes that the Malay ATC need to be monitoring and in contact with, so once they completed their final check in with MH370 they already moved on to the next plane and were no longer keeping tabs on MH370.

The pilot knew this and made sure to quickly swing the plane around to keep it within Malaysian airspace. Doing so is equivalent to shrouding the plane in an invisibility cloak, keeping the aircraft hidden inside Malaysian airspace.

Interestingly, this was a recent change issued only 4 years prior to 2014, and the pilot was fully aware this.

The third reason was either a terrible coincidence or a stroke of dumb luck depending on your perspective.

It took 17 minutes for Ho Chi Minh ATC to realize that MH370 was no longer showing up on their radar display and to subsequently contact Malaysian ATC to ask where the aircraft was.

Why 17 minutes? Why did it take so long? Because this gave the pilot ample time to disappear

Jean-Luc pulled the data from Vietnamese ATC from that night and that particular night was very busy.

On the Ho Chi Minh’s ATCs screens, there were many incoming flights on the bottom right hand of the screen, while MH370 was on the top left.

ATC simply wasn’t looking in that direction and was focused on the other flights, waiting for MH370 to check in with them.

That’s all it took. This gave the pilot a 17 minute lead time to disappear.

So then I ask a question that has been asked since the plane disappeared, did the plane crash into the ocean and if so, how? Because there’s been a valid question of why there wasn’t more debris

And his answer surprised me.

He said the plane didn’t crash…

To be continued in the interview. Jean-Luc discusses in great detail why he knows there was an active pilot to the very end, which 2 neighboring countries saw MH370 that night, but didn’t say anything, how MH370 almost collided into another aircraft that night, why there was very little debris found and what we can expect to recover from the black box and flight recorder if the plane is found.

Thank you for your support! At this time please consider becoming a paid subscriber of Today I Learned Science to support continued content. Each piece takes hours of research and effort to provide high quality content every week and bring you conversations directly with the experts making these groundbreaking discoveries. Your support is deeply appreciated.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Today I Learned Science to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.